If you walk round Muswell Hill, the part of North London where I have lived for nearly 20 years, you’ll occasionally see a man lying on the pavement, fine paintbrush in hand, a full palette of colours by his side. Known locally as ‘Chewing Gum Man’, artist Ben Wilson creates miniature paintings on discarded splodges of gum.

If you walk round Muswell Hill, the part of North London where I have lived for nearly 20 years, you’ll occasionally see a man lying on the pavement, fine paintbrush in hand, a full palette of colours by his side. Known locally as ‘Chewing Gum Man’, artist Ben Wilson creates miniature paintings on discarded splodges of gum.

The discovery of a new ‘piece’ on the ground or a wall brings a smile to my day. Yet unsurprisingly he is hardly known outside the area we live. He’s not got the caché of Banksy. Tourists don’t swap a day at the National Gallery for a walking tour of Muswell Hill Broadway.

When you’ve lived for somewhere as long as I have, however, it is often these sort of intimate details that typify your love of and sense of belonging to a place. Seeing him at work makes me feel at home.

But imagine if Chewing Gum Man were to become the next Banksy. Tourists would be trying to scrape his work off the pavements. Ersatz copycat artists might begin deliberately dropping gum and attempting to emulate him.

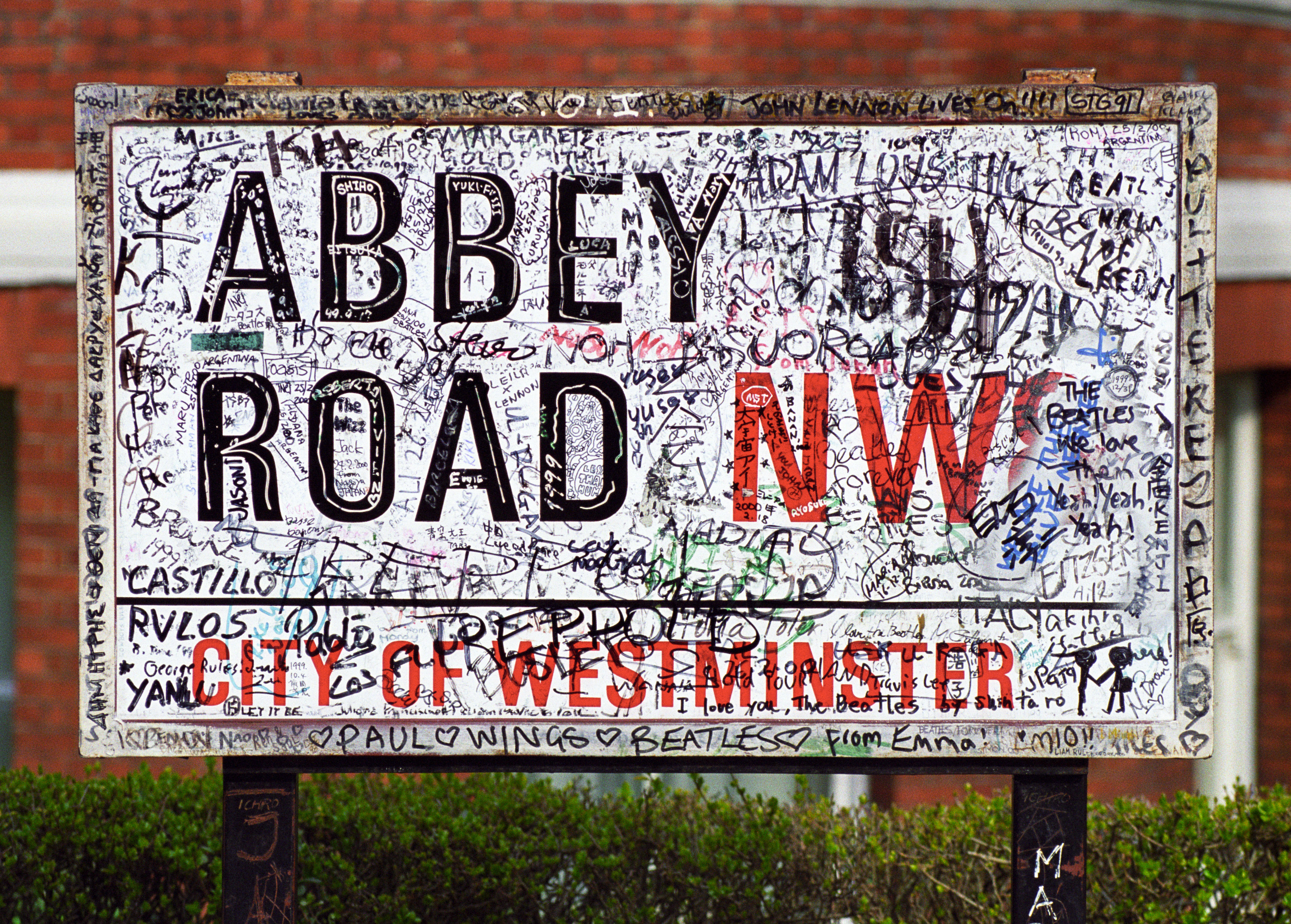

It could become as tawdry as the graffiti-covered walls outside Abbey Road Studios where the zebra crossing is forever queued up with tourists trying to recreate the album cover. Or the bridge in Paris that until last month was groaning under the weight of padlocks (and had spawned numerous copies on other bridges across the world). The place I call home could be ruined by a random facet of its character.

It’s not so far-fetched. The World Heritage City of Georgetown on the Malaysian island of Penang is increasingly covered in street art – some rather wonderful, but ever more of it little more than tagging. Many tourists flock to the ancient sea port these days more for the street food and street art scenes than to admire the actual , often intangible, heritage that got it UNESCO status in the first place.

The result is that where there were 50,000 actual residents of Georgetown, there are now just 9,000. The rental increases and increased prices that have followed tourism mean that, according to Penang Heritage Trust president Khoo Salma Nasution, Georgetown risks losing the very soul that attracts the tourists in the first place.

Traditional craftsmen and traders are being forced out of buildings that their families have lived and worked in for centuries; and boutique hotels are replacing them. “This has happened to many World Heritage Sites,” says Nasution, “where there are more tourists than locals, so tourists end up coming here to see more tourists.”

Barcelona has become so mobbed that the mayor has just put a temporary halt on issuing licences for tourist accommodation in a bid to control the alarming growth in visitor numbers. These days, seven million people visit Barcelona (resident population 1.6 million) each year, and residents are saying the very character that draws the tourists is being eroded as a result.

These pressures can affect more than just the feel of a place. A paper this year by Equality in Tourism researcher Stroma Cole reported that Bali now has 77,500 hotel rooms – up from 40,000 in 2002, and that 65% of the island’s water is used by tourism. According to Cole, the lack of access is increasing the incidence of waterborne diseases. “Despite being Indonesia’s second most prosperous province,” she writes, “it has a higher prevalence of diarrhoea and deaths of toddlers and infants than the national average.”

Penang, Barcelona and Bali are all still beautiful places to visit, yet pressures from the unrestrained growth of tourism risks making them no longer beautiful places to live. In tourism, as in all sectors of society (except perhaps oncology), growth is celebrated with little question. But if the limits are being reached – as the cases of these three cities suggest they are – then what has happened in Barcelona will be a sign of things to come.

Another good example would be Boracay Island, this is soon happening to the place and for its beauty and culture it is such a shame. More public eyes are need, simple issues such as having trash cans on the beach are complicated. money from tourists are seen as more important than the islands eco system. Endangered species on the island have already diminished, coral reefs broken, over fishing, no control.