In recent weeks several stories have emerged of tourism initiatives set up to offer free holidays to medics and other health workers once people are allowed to travel and visit hotels again. These range from #treatourNHS to the launch of the Give Them a Break website.

These campaigns are all inspiring on their own terms, and give me hope that the recovery can be marked by the same generosity and resilience that has been shown through the early stages of the lockdown. This will be increasingly necessary, as maintaining community cohesion and a sense of optimism may become more challenging in the weeks and months ahead.

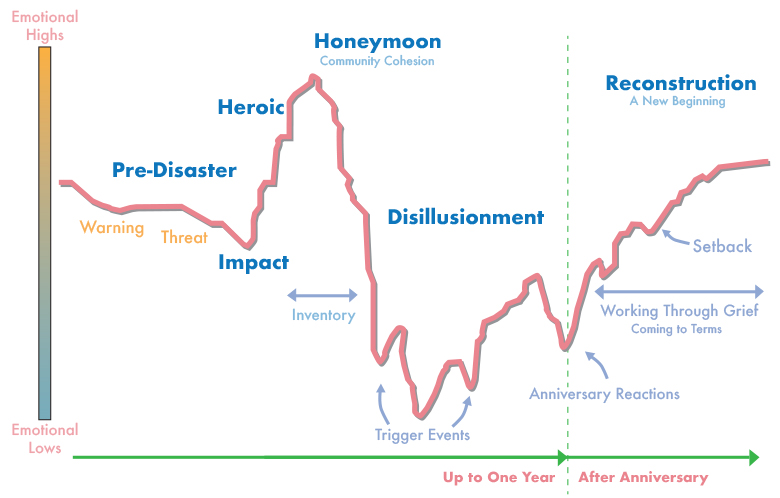

The above graph was shared on Twitter a few days ago by Alex Evans, senior fellow at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation. It’s from the Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters, by Deborah J. DeWolfe (available for free as an ebook). “There are well identified stages of how people feel and act after a huge shock,” says Evans. “We’ve been at the ‘honeymoon’ stage, where lots of us feel a sense of agency and community cohesion – but things will get tougher as we move into the ‘disillusionment’ stage.”

As countries edge closer towards different sorts of recoveries, we need to work as an industry to ensure that we continue to support solidarity through any ‘disillusionment stage’ we may encounter. Over the last week or two I have read countless expert predictions on which sectors will come out the other side in the best state. With a couple of notable exceptions, almost every spokesperson sees their sector as being the one that flourishes. They can’t all be right, and it suggests there is a remarkable amount of confirmation bias at work.

How we communicate matters in these fraught times. Because much as we all want this to be nearing the end, this is the beginning of the story. And while our first chapter has been one of solidarity, the next ones are still to be written. “In moments of change new worlds come into being,” says the Pandemic Response resource guide from the UK’s Public Interest Research Centre, which works with civil society to develop stories and strategies for a more equal, green and democratic society. “The way this crisis is being talked about today will shape the world we emerge into.”

Other crisis communication resources back this up. “In addition to acting with compassion and urgency around immediate needs, we must address the insidious rhetoric that will undermine our long-term shared goals,” explains this COVID-19 messaging guide published by the Million Voters Project. “In a moment of crisis – especially one centred around easily transmitted infection – the messages we must disrupt are rooted in xenophobia, racism, and individualism. More than ever people will be susceptible to fearing ‘the other’ and without a counter-vision and narrative, dominant media and certain public figures will actively or inadvertently stoke that fear.”

No one in the industry wants tourism to end up associated with xenophobia, racism or individualism. And if you think it couldn’t happen, think of the ‘Refugees Welcome, Tourists Go home’ graffiti that became one of the most recurring memes associated with overtourism. Or think of Flight Shame.

Acts of altruism and support for host communities must continue to be our defining characteristics in the months to come. Otherwise we will lose control of the narrative, and stories like the tourists who chartered a private jet to escape down to a luxury villa in the south of France, or rural communities being ‘overrun by second home owners’ risk dominating how the industry is perceived.

It matters therefore that recovery initiatives like those gifting holidays to medics are such generous expressions of solidarity. In connecting hospitals and hospitality, they emphasise the vital deeper truth that the real benefit of tourism is that it is restorative. They remind that there is something intrinsically good about the emotional and mental wellbeing that travel and leisure delivers to those who need it most.

Can we go further?

At the beginning of this week I read an article by the French sustainable tourism expert Guillaume Cromer that takes this concept further. Referring to the news that the southern French region of Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’azur has voted to inject 2.6 million euros to finance the restart of tourism in the region, Cromer asked: “Instead of putting money back into the machine like we used to, couldn’t we… support citizens who are struggling to go on holidays”?

Quite rightly, everyone now wants to thank hard working nurses and doctors. Cromer’s observation challenges us to explore how far we are willing to extend this altruism. Supermarket Staff? Bus drivers? Amazon workers?

What about the long term unemployed? Victims of abuse? The severely disabled? What about those for whom confinement is a permanent state of being?

If we believe that holidays offer a social good that can help people who are broken and exhausted, then surely that remains true always. If so, then the approaches and attitudes embodied in the holidays for helpers initiatives should play a part in defining the tourism that comes next.

All across the country people are desperately keen to leave their homes. The more lucky ones have spent time in their gardens or on their balconies. But the less fortunate? Those in tower blocks without access to balconies? Without internet? Without work? People for whom green space is too far away to access? Or when they do they feel judged for sitting on a patch of shared grass?

In this time of togetherness, we like to think that we are all as one, united in staying at home, dreaming of our next holiday.

But we’re not. Many people are dreaming of their first.

In 2001, Tourism Flanders launched the Holiday Participation Centre to support families across its region for whom poverty meant a holiday was beyond reach. Under the banner of ‘Everyone Deserves a Break’, it now enables 150,000 vulnerable people in the region to get a day away or a short break each year.

In the UK, the Family Holiday Association operates with similar aims. In 2019 it provided short breaks and days out for over 4,800 families across the UK. Just a few weeks ago – in February – it released a new report “The long term impact of a break for struggling families.” The effects on the most vulnerable and isolated of being able to take a short break are profound.

- 83% of families who are impacted by mental health issues see an improvement

- 62% of families do more together than before they went on the break

- School attendance has improved for 85% of families where this was an issue

- 84% of families are less isolated and more able to engage in their communities

- 63% of professionals say the break improves the relationship with families

These are hugely significant figures. Not only do these breaks help the individuals concerned, they make life better for the people and communities they interact with as well.

So let’s take this further. Let’s globalise our solidarity.

We’re seeing lots of stories right now about people keeping the industry solvent by buying vouchers for future holidays. So what if we didn’t just make it possible for people to buy vouchers for themselves, but also for those around the world who never get to experience the joys of leisure and the travel experience?

In 2016, the World Responsible Tourism Award for best innovation was won by US based travel operator Elevate Destinations for a scheme it had created called ‘Buy a trip, Give a trip’. Every trip organized through Elevate Destinations allows a group of local children to visit tourist sites in their own country. In the UK, Responsible Travel now offer a similar Trip for a Trip scheme.

“It is a fact that few locals have the means to visit the very sites that makes their countries attractive to tourists, who spend a lot of money traveling to those sites every year,” said Founder and President of Elevate Destinations, Dominique Callimanopulos. “I felt that offering the same opportunity to local youth sends a message of equanimity, empowerment and equal opportunity to local communities and provides both an educational perspective and feeling of ownership of national resources for those communities.”

Right now there is a lot of talk about bailouts and government funds for tourism. What if governments gave tourism bailouts in terms of accommodation and experience vouchers for people most in need of holiday? Wouldn’t the benefits spread most widely through society if that was the case?

We’re seeing things that were almost unimaginable a few weeks ago entering mainstream discourse. Spain is going to roll out a basic income to support its poorest people. The Pope’s Easter message said it is perhaps “time to consider a universal basic wage”.

How much further do we have to extend our imaginations before we talk of designing societies that ensure everyone – regardless of ability to pay – can access some form of holiday? If we really believe that tourism provides such a fundamental social good, then we should want it to be delivered to all – and especially those who need its restorative benefits most.

I have written here before about tourism’s potential for a far more restorative role, about how doctors in the Shetland Islands have begun prescribing nature cures such as bird walking and hiking – giving people holiday experiences rather than pills. And about how the UK was exploring “the creation of a National Academy for Social Prescribing that will ensure general practitioners, or GPs, across the country are equipped to guide patients to an array of hobbies, sports and arts groups”.

In 2018, the UK Green Party proposed that GDP should be replaced as the measure of societal success with a Free Time Index. Since then we have seen both Scotland and New Zealand say they will be focussing their national development strategies around the provision of wellbeing. Last week Amsterdam announced that its regeneration post Covid is to be framed according to the circular economy principles of Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth.

“Leisure is not a respite from effortful work,” write Ilan Stavans and Joshua Ellison in Reclaiming Travel. “Leisure is an encounter with the intrinsically good, the fundamentally and definitely human.”

Where do we go next?

When the world of tourism opens up again, it will be different. We have lived in a world where capacity always exceeded demand, and yet we kept on adding capacity. Hotels were never full, and yet we built more hotels. Our industry had been growing at around 5% a year for some time.

But over the last few weeks we have been living through an immersive experiment in scarcity. Empty shelves. The inability to book a delivery for weeks ahead. The old and vulnerable now have a special hour at the beginning of the day to go to the supermarket in relative peace, and to ensure they can get what they need.

Imagine the day your country says you can travel again. There will be both a huge pent up desire for escape, combined with a reduced and restricted stock of availability, either because places have ceased business, have not yet been able to open, or have had to implement new measures. Plus almost everyone will be looking to book domestic holidays at the same time.

What will that moment be like? Will it be a frenzy like when Glastonbury tickets are released, with breathless headlines the next day reading “All hotels sold out for November in 24 minutes”? Or will we have prepared for it, and ensured that those who need it most get the chance to benefit from the restoration we provide?

How would we do that?

The old answer was to build more hotels. Convert more rooms to short term rentals. Lay on more flights. Pollute the canals of Venice. Shroud the Himalayas from view.

Things are different now. As the clouds of pollution fade away, we are all being given a chance to see the view. Until now, we thought we were still climbing, climbing a mountain that grew endlessly up towards infinity.

But what if we have actually reached the peak? What if it is up to us to decide?

What if we could decide that 2019 was actually the year of peak emissions?

What if the question we then decide to ask ourselves as we frame our recovery is not “how do we start climbing again?”, but “how do we get back down?”

And how do we do this so that no one is left behind?

You may also be interested in…

- Will 2020 define the future of tourism?

- We should reinvent hotels to be living labs for the future

- Does the COVID-19 emergency mean over-tourism is over?

Definitely the best thing I have read about Post Covid-19 tourism. Asks all the right questions!

Really excellent, thoughtful piece – thank you!!