Reporting from World Travel Market, London

The air at trade shows like the World Travel Market (WTM) is usually thick with the optimism of deal-making—handshakes, new route launches, and the clinking of champagne glasses. But at a packed session on the future of the industry, the mood was different. It was urgent.

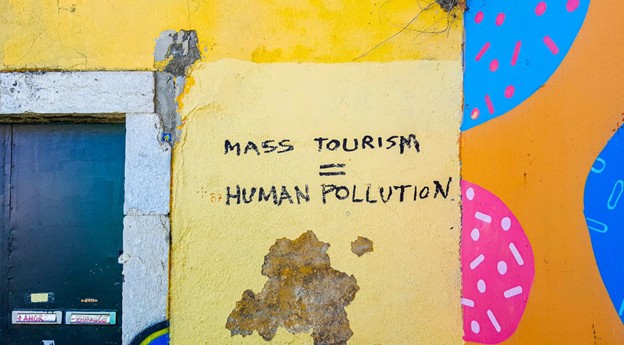

“We are going to talk about the elephant in the room,” announced moderator Dolores Semeraro, silencing the hum of the crowd1. That elephant is the damage of mass tourism—a force that has sparked protests from the Balearics to Greece2. Headlines from the BBC regarding “Bad Tourists” have become commonplace, and local residents across Europe are rising up against an industry they feel is destroying their home3.

But as the session unfolded, it became clear that the threat isn’t just coming from frustrated locals spray-painting “Go Home” on city walls. It is coming from the boardrooms of the world’s biggest banks. The message from the stage was stark: The travel industry must pivot from an “extractive” business model to a “regenerative” one, or risk becoming uninvestable.

The “Trust Deficit”: A Financial Warning Shot

For years, sustainability in travel was treated as a PR exercise or a “nice to have.” Glenn Mandziuk, CEO of the World Sustainable Hospitality Alliance, shattered that illusion with a cold dose of reality from the capital markets.

Representing an alliance of 55,000 hotels and 7 million rooms, Mandziuk revealed a growing rift between hospitality leaders and the financiers who fund them4. “I sit on boards with some of the leading financiers in the world, the largest banks, CEOs,” Mandziuk confessed5.

Their message to him is chilling: “In our world we don’t believe you’re taking it seriously. And as a result, we put our money elsewhere and you don’t even know it”6.

The industry is suffering from a massive communication failure. While hotels measure success by RevPAR (Revenue Per Available Room) or arrival numbers, they lack a common, data-driven approach to measuring their social and environmental impact7. Without this data, the industry cannot prove its value to the communities it operates in, creating a “trust deficit” that threatens its social license to operate8888.

Mandziuk’s solution is “Net Positive Hospitality”—a philosophy where the industry gives back to the destination more than it takes9. It is no longer enough to be neutral; the industry must be a contributor. “It’s about talking, not about GDP and how many jobs, because that doesn’t fix the potholes on the street,” Mandziuk argued10. If the hotel isn’t helping to fix the community center or the road, the community—and eventually the investors—will turn their backs.

The “Disneyland-ification” of Reality

If the financiers are pulling back because of risk, the travelers are pulling back because of a degradation of product. The panel argued that “extraction”—mining a destination for maximum volume—eventually destroys the very product being sold.

Carol Savage, CEO of Not in the Guidebooks, pointed to the “Instagram effect” on destinations like Medellin, Colombia111111. She described how the city is “bowl shaped,” with two distinct sides12. One side, popularized by social media influencers, has become “almost like an Instagramable place”13.

Photo by Mark de Jong

“For me, that was just like going to a not very nice Disneyland,” Savage noted14. In these over-touristed zones, authenticity is stripped away, replaced by people selling trinkets to extract as much money as possible from transients15.

This leads to “leakage”—not just cultural, but economic. When tourism is mass-produced and centered on big resorts or international chains, the money “leaks out” of the country rather than circulating within the local economy16. Savage argues for a model that keeps wealth within the destination, connecting travelers directly to local artisans and communities.

This isn’t just charity; it is future-proofing. As Savage noted, “Experience-led tourism is what propels people to travel”17. Travelers want to connect with the people who “make food for the community” or run the local distilleries18. If the local character dies, the market dies with it.

The Tech Fix: Engineering the Flow

Can we engineer our way out of this? Gavin Brookin, Managing Director of Tootbus UK, believes technology can at least stop the bleeding. Operating in London, a city where traffic is a daily battle, Tootbus has had to rethink the “machine” of tourism19.

Brookin detailed a high-tech approach to dispersion. Using AI and real-time data, the company created “Toot Walks”—self-guided audio tours designed to physically remove passengers from buses in congested areas202020. When the bus approaches a gridlocked zone, the driver can advise passengers to hop off, take a guided walking tour through the Royal Parks, and pick up the bus at a different stop later21.

“We prevent that damage being done by mass presence, by pressure on the city,” Brookin explained22.

Furthermore, they are tackling the carbon footprint head-on. Brookin revealed that Tootbus is retrofitting 25-year-old buses with electric engines—a prime example of the circular economy23232323. “We believe in the circular economy… that bus is 25 years old,” he said24242424. While competitors lag behind with no electric fleets, Tootbus is proving that legacy infrastructure can be modernized25.

But while electric buses and AI routing are vital tools, the session’s keynote speaker argued they are merely treating the symptoms, not the disease.

The Paradigm Shift: From Machine to Garden

The emotional and intellectual core of the session came from Anna Pollock of Conscious Travel. A veteran with 50 years in the industry, Pollock argued that we are trying to solve modern problems with an obsolete mindset26.

“We’re behaving like adolescents,” Pollock observed of the human race27. We want the freedom to drive the car, but we refuse to clean up our room28.

Pollock outlined a massive shift from a “Machine Paradigm”—where the world is a collection of separate parts to be exploited—to a “Living Systems Paradigm”29. In the Machine story, nature is an “it”—a resource to be used30. This worldview assumes we can extract endless value without consequences because we are separate from the environment31.

“I find it really sad when you see regenerative thinking in tourism reduced to… leaving the place better than they found it,” Pollock said32. “We simplify it… [Regeneration] is about creating the conditions for life to flourish”33333333.

This is the difference between “Sustainability” (doing less harm) and “Regeneration” (enabling life)34. It requires a total redefinition of success, moving away from infinite growth curves toward health, adaptation, and community well-being35.

“We are living at the very momentous period in history when one system is actually in decline… but another world, another way of being is being born,” Pollock told the hushed room36.

The Original Regenerators

The irony, as the session concluded, is that this “new” way of thinking—seeing the world as a living, connected system—is actually the oldest worldview on Earth. The Indigenous Tourism panel provided the practical blueprint for Pollock’s philosophy.

Tamara Littlelight of the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC) introduced the “Original Original” accreditation37. This mark of excellence ensures that tourism businesses are at least 51% Indigenous-owned, guaranteeing that the economic benefits—and the narrative control—stay with the community38.

“We are the original stewards of the land,” Littlelight reminded the audience39. “So what better way to learn Canada than from us”40.

Littlelight highlighted that demand is surging—one in every three international travelers to Canada is now interested in an Indigenous experience41. However, this must be managed carefully to avoid “cultural appropriation”42. The “Original Original” mark acts as a shield, ensuring that travelers support authentic cultural revitalization rather than performative exploitation43434343.

Similarly, Sharzede Datu Salleh Askor, CEO of the Sarawak Tourism Board, shared a poignant example of cultural regeneration through the Rainforest World Music Festival44. The festival wasn’t just about selling tickets; it was about saving the sape, a traditional lute instrument that was on the verge of extinction45.

“Now that instrument has become a trend… it keeps it alive,” Sharzede explained46. By giving the culture a global stage, they inspired the local youth to pick up the instrument again. “Imagine a Grammy Award artist performing together with our indigenous artists… To them it’s a wow thing. It gives them the confidence,” she said47.

This is the “Garden” paradigm in action: tourism acting not as a mining operation, but as a nutrient that feeds the local roots, allowing the culture to grow stronger.

Our Choice Between The Machine or The Garden

The industry stands at a crossroads. Down one path lies the “Machine”—a world of overcrowding, investor skepticism, and “Disneyland-ification.” It is a world where success is measured solely by the number of bodies moving through a turnstile, regardless of the damage left behind.

Down the other path lies the “Garden”—a complex, slower, but ultimately more profitable world of net-positive hospitality and indigenous stewardship. It is a world where success is measured by the health of the community and the trust of the financial markets.

As the attendees filtered out of the auditorium, the words of Anna Pollock lingered. She quoted a poem to explain the fluid, connected nature of this new reality: “We are more weather pattern than stone monument”48.

The climate of travel is changing. The only question remains whether travel companies will adapt their structures to survive the weather, or be washed away by the rising tide of scrutiny. The “business as usual” license has officially expired.